4. The Rule of the Octave

"One of the most striking features of eighteenth-century music theory is the so-called Rule of the Octave. It stems from thoroughbass treatises denoting standard chord progressions on ascending and descending bass scales. An “inventor” of the Rule of the Octave can hardly be traced, although the lutist and guitarist François Campion claimed the honor in 1716. The Rule of the Octave (hereafter RO) acts like a living organism: various versions circulate throughout the century. The RO has been used as a tool for keyboard (or plucked strings) accompaniment and improvisation. In order to grasp the proper chords automatically, apprentices have been required to play the RO in all major and minor keys.

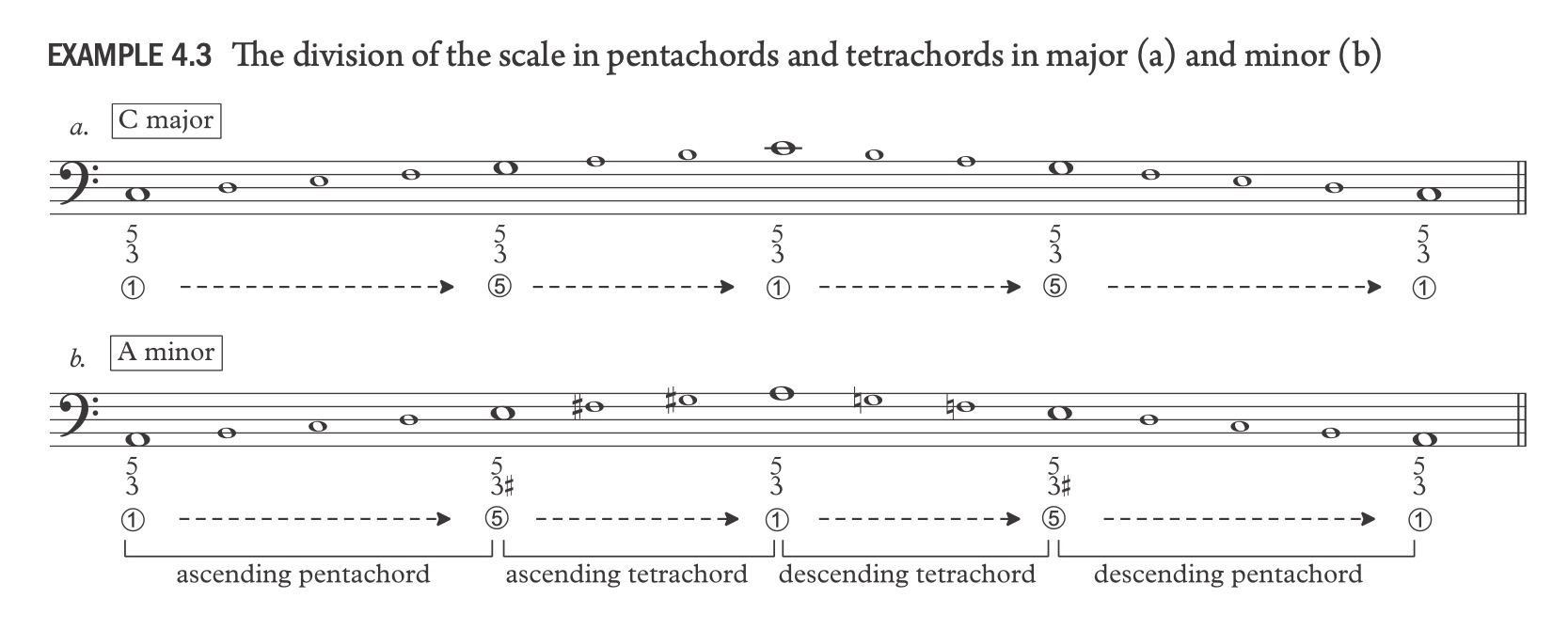

The principle of the RO is simple. Each bass tone of the major and minor scale requires a unique chord realization. Conversely, each chord or chord progression occupies its own place in the scale. In this way the specific chords and chord progressions that are derived from the Rule of the Octave establish the key. Many teachers, theorists, and composers have warned against a thoughtless application of the RO. Indeed, the RO merely provides a concise harmonic “vocabu- lary” that leaves room for many exceptions and variants. Moreover, it does not address bass leaps at all. Nevertheless, the RO appears to be an indispensible attribute for understanding eighteenth- century harmony. It even proves its value in nineteenth-century music, although in a more lim- ited fashion: the harmonic developments of the Romantic style go far beyond the simple chord progressions provided by the Rule of the Octave."

(IJzerman: Harmony, Counterpoint, Partimento page 78)